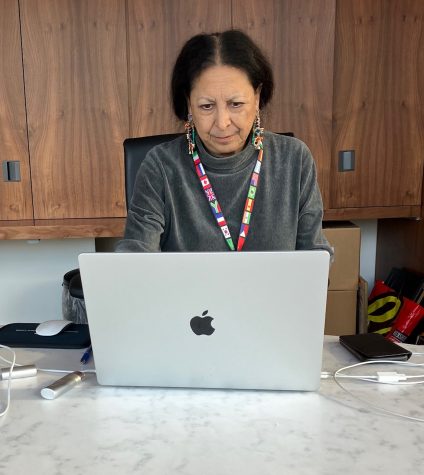

Chancellor Judy Miner: a lifetime of learning

Judy Miner (middle) and her two sisters, Dottie Lagrand (left) and Janice (right), celebrating Dottie’s retirement in 2015. Lagrand refers to Miner as “the rock of the family” and said she looks forward to taking more trips with her younger sister once she’s retired. (Photo courtesy of Dottie Lagrand)

November 19, 2022

Foothill-De Anza Chancellor Judy Miner remembers desperately wanting to go home.

When she was 2 years old, her family moved from the Bernal Heights neighborhood of San Francisco to the Excelsior District. She stood on the porch of her family’s new home and decided to set off down the front steps.

“I got as far as the seventh house down the street, and for a 2-year-old, that’s a long way to go,” Miner said. “I panicked everybody.

Miner eventually found her place in the Excelsior District, warmly remembering her childhood there. She was the youngest of five children to a Mexican-born mother and a Guam-born father.

Her father left Guam with a naval family and immigrated to the Bay Area in his teens, working at the Mare Island Naval Shipyard and San Francisco Naval Shipyard. Her mother’s earliest memory, after coming to the U.S. illegally, was picking lettuce in Southern California.

“I think it was really rough for my mother to get married at 17 years old and to have five children,” Miner said. “But I think as a family, knowing that my mom put up with so many stressors made us feel very appreciative of the love that we grew up with and that she cared deeply about us, as did our dad.”

Her mother chose not to speak Spanish with her children out of the fear that they would grow up with an accent. Miner said she understood where her mother was coming from.

“There was so much prejudice against people who didn’t speak English,” Miner said. “(My mother) was of a generation that felt you would confuse children by speaking more than one language, as opposed to what we now know about children doing well in multi-language acquisition. It was very much the sense of, to be an American, you had to abandon anything that looked like the other –– in this case, anything that was a part of her Mexican heritage.”

Despite her mother’s concerns, Miner said she fit into the Catholic schools she attended.

“I think it was more about Catholic identity,” Miner said. “Having those religious traditions was such a unifying experience for us.”

Miner described herself as an avid reader throughout her childhood and said she “always loved” school. The inspiration to pursue a career in education came in the first or second grade when a neighbor asked her what she wanted to do when she grew up.

“I told them I wanted to be a teacher,” Miner said. “That person said, ‘We always need teachers.’ It always stuck with me.”

Miner’s love of learning led her to enroll in Lone Mountain College in 1970, becoming the first in her family to pursue higher education. Her parents dropped out in the fifth and 11th grade respectively, and her older siblings took different paths after graduating high school. Nonetheless, Dottie Lagrand, Miner’s older sister, said the family was “very proud.”

“It was wonderful to see her succeed in life through education,” Lagrand said. “Judy was self-educated, and she worked her way through college by self- sacrifice.”

One challenge Miner faced while seeking higher education was not being able to afford it, as her parents did not pay for her to attend college.

“My mother was adamant that they would give me nothing to go to college because none of my siblings went to college,” Miner said. “They said, in the sense of treating everyone equally, we’re not paying for it.”

Instead, Miner relied on scholarships, day-time jobs at Lone Mountain and a night job at Macy’s in credit authorization. She recalls adhering to a strict budget to afford her books and basic necessities.

“That felt like real stress to have to worry about those things,” Miner said.

“There was no extensive wardrobe, no eating out, no vacations. I hadn’t learned how to drive because it was going to be too expensive to even worry about a car.”

Miner devoted herself to her studies, packing her schedule with courses. She graduated with a bachelor’s degree in history and French in 1973, and would later return to receive a master’s degree in history in 1977.

Miner worked as a registration assistant and registar at Lone Mountain before becoming registrar at the University of San Francisco School of Law. In 1979, at the age of 27, Miner started her community college career as the Dean of Admissions and Records at City College of San Francisco. She described it as a difficult transition.

“I was coming from only a few years of admissions and records experience in Catholic schools,” Miner said. “Those are so different from a public institution with 30,000 students run by an elected board of trustees.”

There were also some painful lessons, one of which she learned on her first day.

“I was very excited to go say hello to the Vice President of Student Services that I reported to,” Miner said. “And he just looked at me and said, ‘You shouldn’t have gotten this job, but the president keeps hiring skirts.’”

During her first year, Miner faced reprisal from her assistant registrar, a male colleague who had applied for her position and didn’t get the job. Miner said he threw out reports that she needed to review, and the women in the office who looked out for her had to fish those reports out of the trash.

“It was such a wake-up call for me about people who weren’t necessarily going to support my being there, or support women and women of color moving into positions of administration,” Miner said. “There was a sense of entitlement for people who had been in organizations, because obviously I was an outsider.”

Miner spent five years at the City College of San Francisco before becoming the Dean of Matriculation at De Anza College. She filled multiple positions in student services and was later appointed the Dean of Academic Services in 1997, a shift toward the instruction side of administration.

Martha Kanter, the president of De Anza at the time, eventually made Miner the vice president of instruction. Kanter described Miner as a “systems person” who communicated well with her colleagues and designed on-campus programs to integrate various departments.

“There were student supports like Academic Affairs, the integration of what unions demand (as well as) what the faculty and staff and administrators would like to accomplish,” Kanter explained. “There were lots of differences, and she was really good at diving into the differences and coming up with solutions that really helped everyone win.”

After serving as vice president of instruction for nine years, Miner left De Anza and became president of Foothill College in 2007.

When Miner arrived at Foothill, 12% of students were Latino — this increased to 25% by the time she left the university. During her tenure, Miner worked to make Foothill a more “welcoming kind of atmosphere” through several efforts to assist a more diverse range of students.

“(My vice president of student services) did a great job in hiring more people in student services, so that there were so many more languages represented there,” Miner said. “We also did ‘Ask Foothill,’ one of the earliest chatbots on the website that translated (answers) into Spanish so students who were English language learners could better understand. There was also an opportunity to bring in the Family Engagement Institute because there had been a very large grant that has actually lasted until this year.”

When Miner applied to be chancellor, she told the forum and board that she wanted to improve student diversity and equity. But in recent years, because of George Floyd’s murder and more studies regarding inequities in higher education, she has reframed the issue.

She said that among underrepresented groups in education, she strives to close the “opportunity gap” instead of the “achievement gap,” as it was previously referred to throughout her career.

“We’re all about pathways, creating opportunities and really tapping student potential,” Miner said. “Yet, we ourselves are products of a system that has so much racial bias in it and historical inequities that we’ve just lived with and have not necessarily questioned. I think we sometimes are coy in our terminology, which is why I’m so proud of our board for calling out racism and systemic barriers in their priorities for the way the district needs to move forward.”

When Miner became chancellor in 2015, she also confronted issues with the district budget from the effects of the recession. She said the district has done “really well” with its fundraising budget, but the ongoing budget may still be a problem.

“We have spent down the stability fund that [we received] probably 10 years ago, which was about $30 million,” Miner said. “It was so important to us to save positions over the intervening years to actually be able to give raises even when the state may not have given us a COLA (cost of living adjustment). I hope part of my legacy would be managing the resources that we had so that we bought ourselves time to hold on to people.”

Enrollment was another problem that was exacerbated by the pandemic. In September, Miner abruptly announced that masking would be optional, later writing in an email that she feared “losing enrollment to neighboring districts as a result of the masking mandate.”

Now, Miner said, the enrollment is “stabilizing,” in large part because of a recruiting strategy that brought in international students from new markets.

“We’re not as dependent on students coming from China as we had been before, and we had a stabilization this fall with our international students,” Miner said. “And because we had raised the tuition, we actually have a little more income from them. That’s helpful because no matter what the state does, any revenue we get from non-residents we get to keep.”

Miner points to the hiring process for the Reimagining Transfer for Student Success program that she launched in September 2021 as a turning point. She said she felt the need to set the tone as chancellor by making way for new leadership.

“I thought to myself, ‘I should really be a role model for the reimagining by stepping aside at this time,’ and allowing somebody new to come in and to have a honeymoon period for tackling some of these tough issues with fresh energy,” Miner said. “I think (those) of us who’ve been around for a while carry a certain baggage with us.”

Laura Casas, the vice president of the Foothill-De Anza Board of Trustees, said the board is working with a chancellor search committee made up of community members and interest groups on campus. She estimated that the board will have chosen a new chancellor by the middle of next spring.

Casas said that she hopes the next generation of leadership can carry on Miner’s legacy.

“Her soul and spirit is about equity and inclusion,” Casas said. “That’s definitely something I am going to be looking for in the next chancellor: her passion.”

Despite her September 2023 retirement from the district, Miner will stay on the boards of several other groups relating to education, including the board at the University of San Francisco and nonprofits such as YearUp.

As a self-described “opera fanatic,” she said she plans to travel internationally to enjoy more shows.

“My favorite opera cities are Paris, London and Sydney,” Miner said. “To be able to go back to them since the pandemic will be pretty exciting.”

She said her last message to Foothill-De Anza students is to believe in themselves.

“I think so many of our students may have a more limited view of what they can do in part because of just their own exposure — or lack thereof — to different possibilities,” Miner said. “There is so much love and commitment here. This is an amazing district and the colleges have done an exquisite job of hiring people who really believe in students.”