Umoja faculty, students unsupported, unheard by De Anza College administration

August 20, 2020

De Anza College faculty members and students claim they have felt no support for the Umoja program from upper administration, leaving Black students isolated and not invested in.

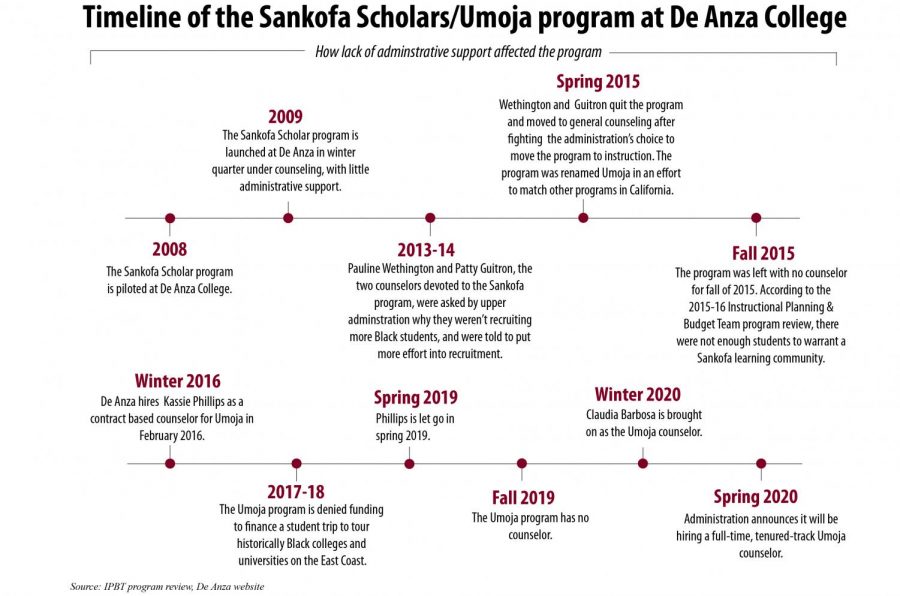

The program, formerly known as the Sankofa Scholars, began in 2008 with a pilot, and then was officially launched in 2009. It aimed to help Black students succeed academically at De Anza, as well as provide a support system for students.

But the journey to starting the program took a couple of years because of a lack of funding and administrative support.

Ulysses Pichon, a retired English professor and one of the founders of the program at De Anza, said that Black faculty on campus would meet to discuss supporting and assisting Black students, but a program never surfaced.

“It seemed like we would talk about it and there would be good intentions and good insight, but because there was no way to fund anything, there was nothing done,” Pichon said.

The administration did not supply a budget to begin the program, which forced faculty to work with minimal funding.

“There was no administrative push behind it in any way,” Pichon said.

Jean Miller, former English instructor and namesake of the Jean Miller Resource Room, along with Pichon and other faculty members, worked around the funding issues by placing students within classes together that were taught by professors who were already employed.

Students took intercultural studies classes together, as well as English classes, where they were supported by faculty in and outside of class.

“I was never interested in my material,” said Sherrell Robinson, 23, nursing major. “Reading a book by an African American woman, I was like ‘hmmm, let’s see what she has to say.’”

The Sankofa Scholars program used the budget they had for field trips to places like the Museum of African Diaspora, where students learned about their culture and bonded over their shared experiences.

Pichon said the administration gave unneeded attention to a small group of students on campus. He said this was part of the reason that the administration did not take action to support the program.

“They came to presentations that we did you know, they showed up and they applauded what we were doing,” he said. “But it hardly went any further than that.”

Reorganization

In 2008, Pauline Wethington, counseling, became the full time Sankofa Scholars counselor. She worked closely with Patty Guitron, counseling, who, at the time, was the Student Success and Retention Services and First-Year Experience director.

“We had built such a strong community that year after I took it over,” Wethington said.

The program was housed under counseling and SSRS, where it received part of its budget.

Wethington and Guitron expanded the program to connect students with historically Black colleges and universities and other academic prospects, as well as an increased effort to support students’ emotional wellbeing.

In the 2013-14 school year, Wethington and Guitron were called into a meeting with Christina Espinosa-Pieb, vice president of instruction, and Brian Murphy, former president of De Anza College.

Guitron said that they were asked why they weren’t recruiting more Black students. She said she felt that the effort to recruit more Black students was only being headed by her and Wethington.

Espinosa-Pieb has not responded to requests for comment.

Wethington and Guitron asked for a year off of the program to focus on building it up, and have the current students in the program to be placed with an FYE counselor as a cushion.

They were told no by upper administration, and to use the Office of Outreach to recruit more Black students because of the number of students that it recruited each year.

But Guitron said that the numbers the college provided were not always accurate and were often dated, or were not all Black students.

As of the most current program review only 65% of those counted as part of the program, self-identified as Black or African American during the 2017-2018 instructional year.

“I wish we could hold them more accountable,” Guitron said. “When you say you have 100 black students, are they all really black students? And are they still here? Or did they transfer five years ago?”

In an attempt to recruit more Black students and Sankofa Scholars students, Guitron and Wethington visited high schools with higher Black student populations to promote De Anza College.

Thomas Stinson, 24, former Sankofa Scholar and De Anza alumni, who graduated from Branham High School, said that he learned about De Anza’s program through one of those outreach efforts.

“They actually came onto my campus and just gave a little bit of information,” said Stinson.

In 2015, Wethington and Guitron were pulled into another meeting with upper administration, including Stacy Cook, former vice president of student services and Rowena Tomaneng, former associate vice president of instruction.

Cook and Tomaneng were unable to be reached for comment.

They were told that the program was going to be moved from counseling to the Office of Instruction to provide more money.

Murphy and Espinosa-Pieb were also a part of the decision to move the program to instructional.

However, Murphy said in a recent interview with La Voz that the move was not because of funding.

“We then wanted to bring together the various learning communities,” he said. “It was to have the learning communities be in the same area and able to share best practices and share their ideas.”

There are currently five cohorts under instruction, including the Umoja program.

Wethington and Guitron fought the move, because they felt that the program was better suited for counseling, where students were not only advised academically, but were supported emotionally and mentally as well.

Guitron questioned the legitimacy of the budgetary claim because they had been able to run the program effectively without much assistance from the district.

Wethington continued to push back against the move.

“It fell on a deaf ear, as though a Black voice was not really heard,” she said.

After Wethington and Guitron threatened to leave the program if it was moved, the administration said that it would still be moved, even if they left.

Wethington and Guitron chose to leave, rather than support the program’s move.

“It was kind of a slap in the face,” Guitron said. “They both went, ‘Okay, bye.’ I’ve been doing programs for 15 years up to that point, and so I was heartbroken by that. My whole counseling career has really been around these programs.”

Wethington said that even though she left, she was still there for Black students.

“I’m not abandoning you, I’m not leaving you,” she said. “I am still at De Anza College but I will not be dictated and told as a full tenure-track, Board approved faculty person, that they’re going to uproot me and tell me that I’m going to do X, Y and Z without me having a voice. I didn’t feel respected at the time as a person of color.”

Since the switch, Wethington said Black students have felt isolated because of the lack of awareness of resources available to them.

“This is where the big gap became,” Wethington said. “They didn’t know there were other Black counselors at De Anza College.”

Stinson said before the changes, the environment in the program was better.

“We had our own personal counselors that we could go to anytime we needed assistance with anything, as well as resources such as computers, laptops, a work environment that was quiet and well kept,” Stinson said.

The program’s former location in the Registration and Student Services building, above the bookstore near counseling offices, had a dedicated smart room with computers and the internet according to the 2014-2015 Counseling and Student Success – Student Services Program Review Reflection.

After the restructuring of the program in the 2014-15 school year, they were relocated to a smaller, harder to access location in the Learning Center West building.

“Currently the SSRS Center houses four cohort programs and has exceeded the room capacity during peak hours and exceeds room capacity,” according to the most recent Instructional Planning and Budget Team program review. “Currently, the space provided is at capacity during peak times and presents a safety hazard. Not enough tables or chairs or space to accommodate them all so many use the LCW hallway to meet and work on projects.”

The new location’s small space reduced the number of students engaged in the program, Stinson said.

“Once they were able to find it, it’s just like, ‘this is too small to get a lot of stuff done so I’m just going to continue working in my own area,’ so they slipped out on that,” Stinson said.

The Budget

The Umoja program is funded in part by the Foothill-De Anza College District budget under Restricted and Categorical funds, which were matched by the state under the 2012 Seymour-Campbell Student Success Act.

Before the program moved to instruction, it was part of a group known as Student Success and Support Programs that were overseen by Student Services Planning and Budget.

This group encompasses Puente, a program designed to assist Latinx students, First Year Experience, dedicated to first-generation college students and Umoja.

Each of these programs interacts with Summer Bridge which helps first generation college students set up educational goals and transition into college.

The current plan, known as the “Student Equity Plan,” combines the Basic Skills Initiative, Student Equity program and SSSP under Student Equity and Achievement intended to orient the state’s community colleges toward a guided pathways model.

Since the reorganization, the program has been housed under the Instructional Budget and Planning Team.

The Umoja program receives funding from the DASB Senate for student employees and conference trips which have fluctuated throughout the years since it was first supported in the 2013-2014 fiscal year.

In addition, from 2016 to 2019, the program received the majority of its funding from the Office of Equity.

In the last De Anza Associated Student Body budget, the Umoja program funding reached its lowest point, eliminating funding for student workers, known as peer advisors.

Robinson said that she had pushback when requesting funds from the DASB Senate to fund conferences for the program.

“There was this whole debate about if we deserved it or not,” she said.

Now, Robinson said she has made allies on the board that are willing to help her apply for funding and meet the DASB Senate funding criteria which was changed during the 2019-20 budget fiscal year to be more restrictive.

Student experience

Many students have praised the Umoja program for building a sense of community and helping them digest course material, but they also said there have been many setbacks to the program’s success that have deterred student participation.

One of the main offerings of the program is campus tours to potential transfer colleges such as UCLA and UC Berkeley.

However, previous budget cuts have resulted in fewer students having the opportunity to attend.

“Who wants to be part of this amazing program, everything is all good on campus, but then when it’s time to go to colleges or go to these conferences more than half of us can’t even go?” asked Robinson.

Robinson said new essay assignments were created to try to whittle down the students who could attend the UCLA campus tour in 2018.

She said students had to hold their bags in their laps on the way back from the airport and according to an email she provided, three to four students were assigned per hotel room.

Another issue stems from a lack of opportunity to advertise, said Justice Merriman, 19, sociology major and Umoja peer advisor.

“There’s not a lot of students that are aware of our program right now,” she said.

Robinson said because Umoja cannot participate in club day, student outreach has been impacted.

“They don’t consider the Umoja program as a club,” said Robinson. “So when it’s club day, we don’t get to table and we don’t get to do the sharing of the program and everything.”

Robinson said that she passes out flyers for the program and reaches out directly to Black students on campus as their main form of on campus outreach.

Tamara Williams, 26, alumni and 2020 commencement speaker for De Anza, said that until recently, she had no idea what Umoja was.

“I didn’t know about the Umoja program until I was about to graduate,” said Williams. “And that really sucks because that would have been nice to have a safe place for me.”

2015 to now

When the Umoja program transitioned from the counseling division to the instructional division, the district hired a contract based Umoja counselor to head the program.

Under this contract, the counselor position would have to be renewed at the end of each school year, as opposed to a tenured position.

Kassie Phillips, former Umoja counselor and Umoja graduate herself, remained at De Anza College for three years, and was then let go in spring 2019.

Phillips said during her time within the program, she felt welcomed and supported by faculty members and the Black community on campus but felt a disconnect with upper administration.

During the 2015-16 school year, there were not enough students to warrant a Sankofa learning community, according to the most recent IBPT program review.

Because of this, Umoja students were no longer placed in classes together as a part of the program.

In the 2017-18 school year, the Umoja program requested funding from the district to finance a student trip to tour HBCUs on the East Coast.

They were denied the funding from upper administration, and when they asked the DASB Senate to fund it, the administration said they could not use the almost $30,000 approved by the senate either.

Phillips said she believed this was because of a drop in enrollment, as well as the measured success of the program, which the upper administration viewed as low.

“We get the least amount of everything, and they want us to have the largest results,” she said.

Because of the lack of funding, Phillips said that she had students leave De Anza and attend other colleges, where they saw more opportunities for Umoja students.

Phillips said she also believed that she was let go in spring 2019 because she was hired on a contract basis and the administration needed to make easy program cuts due to a budgetary crisis.

“I feel like I was a casualty of war that I did not wage,” she said.

Leaving the Umoja program and its students was emotional, Phillips said.

“It was the hardest thing I’ve probably done in my life, just because I didn’t feel like it was warranted,” she said.

Phillips is currently a Umoja counselor at Laney College.

The program was left without a counselor for fall quarter 2019 until Claudia Barbosa took over the position in the following winter quarter.

The program is now in the process of hiring a counselor that was announced in spring 2020.

The previous counselor, Claudia Barbosa, moved to another college within the Umoja program in August.

Barbosa declined to speak on the record about the move.

Phillips said that she feels that the hiring of the tenure-track counselor is in response to the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, in an attempt to show that administration is listening to Black students and faculty.

“When it was just my voice, my voice wasn’t enough,” she said. “When my students were talking, it wasn’t enough.”

Guitron said she had mixed emotions about the new hire.

“I’m glad, but I’m kind of pissed at the same time, because how many years were we screaming like, ‘Hey, we need help, love it, give us support,’” she said. “And it was like, ‘No, figure it out.’ And now all of a sudden, ‘oh, yeah, no, we’re gonna do what we can to support Black students.’”

The administration is still in the process of hiring the tenured Umoja counselor, and it is unclear who is acting in that role during the hiring process.

“I just hope that they realize how important this program is, not only to me, but for the future students of De Anza College,” said Robinson.