Base affirmative action on economic background, not race

April 21, 2014

To maximize the positive effect Affirmative Action has on minority groups, the California legislature should take into account a student’s economic background in addition to his or her ethnic background.

Although race-based affirmative action was necessary in the past in order to correct historical injustices, it’s now time to combine race with class criteria to ensure low-income students from all ethnic backgrounds get better representation in public universities.

This way, a single ethnic group will not be discriminated against.

The economic criteria will support those who have fewer opportunities to pursue a higher level of education because of their financial background, not simply because of a racial generalization.

Affirmative action was first intended to help disadvantaged students get admission into elite colleges, before being prohibited by the approval of California Proposition 209 in 1996.

Californians have debated whether affirmative action denies deserving students an equal opportunity to higher education.

Many Chinese-American groups stalled the Senate Constitutional Amendment No.5 (SCA-5), a measure designed to reinstate admissions-based affirmative action at California’s public universities, according to San Jose Mercury News.

They believed university seats at elite public institutions such as UC Berkeley and UCLA will be taken away from Chinese-American students and given to African-Americans, Latinos and other Asian or Pacific Islander groups who have historically been admitted in fewer numbers.

UC admission data for 2013 revealed 78% of Chinese-American freshman applicants were admitted as opposed to 55% of Latino applicants and 45% of African-American applicants.

Admission rates for Asian minorities such as Filipino-Americans (57%) and Pacific Islanders (48%) reflected a similar gap.

Given their historically high rates of admission, it makes sense Chinese-Americans are opposed to SCA-5.

They pointed to Princeton University research that found Asian-American applicants needed much higher SAT scores than all other groups in order to gain admission into elite universities.

“The way Asian-American students are treated … is a gross violation of the 14th Amendment(which requires equal protection under the law to all people),”said Shien Biau Woo, co-founder of the Asian-American political action committee.

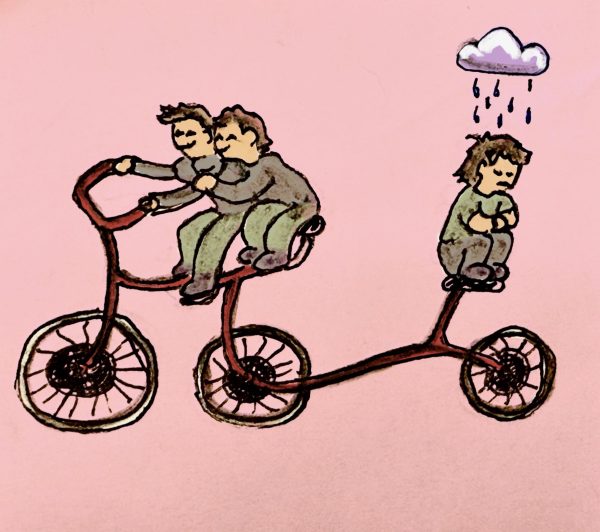

Unfortunately, the debate over affirmative action and SCA-5 is driving a wedge between minority ethnic groups instead of bringing them together.

One important factor has been largely ignored by all sides in this controversy surrounding affirmative action — economic and class inequality, which is rapidly widening in California.

A study of the country’s 50 largest cities by Alan Berube at the Brookings Institution listed San Francisco (2), Oakland (7) and Los Angeles (9) among the top 10 in gaping income disparities.

San Francisco showed the largest increase in income inequality between 2007 and 2012.

Income inequality should be linked to the issue of affirmative action in college admissions as well.

Combining race with class criteria will allow low-income students from all ethnic backgrounds to get better representation in public universities.

In a nationwide 2005 study of highly selective institutions, William Bowen, former president of Princeton University, showed underrepresented minorities increased chances of admission by 27.7 percent, but being in the bottom income quartile had no positive effect.

Universities do not put enough effort into boosting the representation of low-income students, even from the same ethnic groups.

Joining hands to promote affirmative action on the basis of both race and class would be a more effective use of Affirmative Action – so the measure will serve its purpose in this day and age.