In the wake of Black Lives Matter, some students call for defunding campus police while administration has other plans

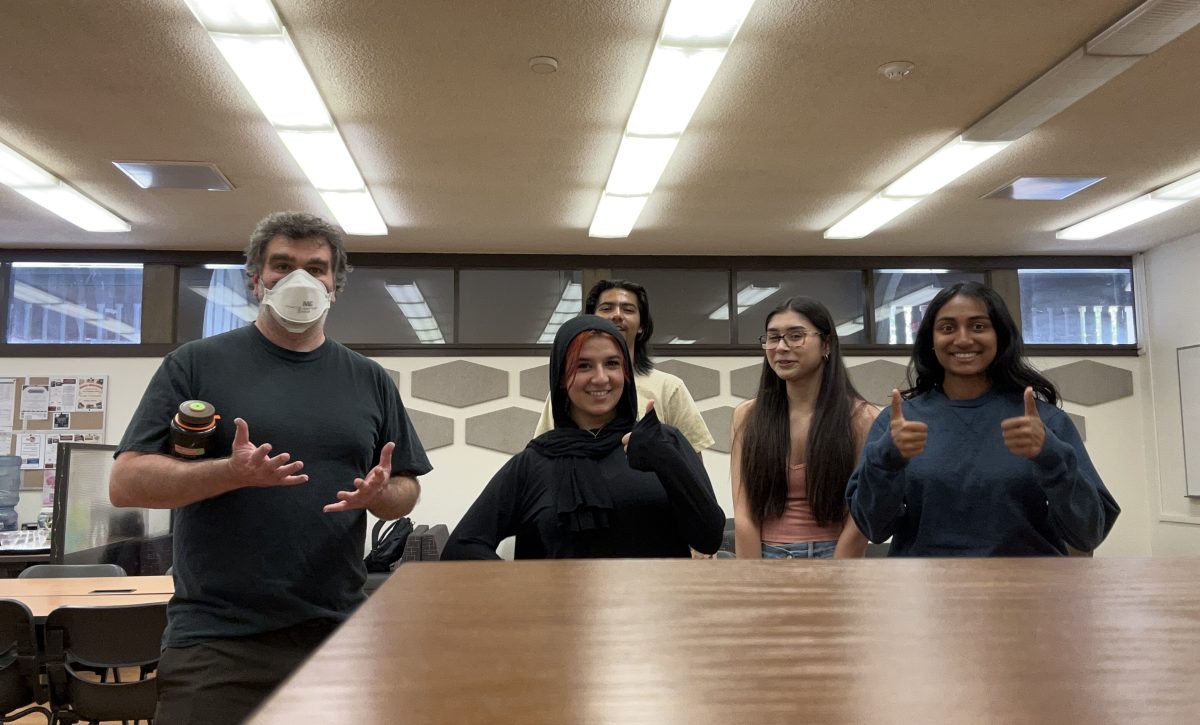

View from outside of the De Anza police station. Campus security and other administrative tasks are managed by a handful of officers, unarmed community service officers and part-time student employees.

December 12, 2021

Even though it was over a year ago and 2,000 miles away, George Floyd’s murder continues to reverberate throughout the country. The timing and footage of his death renewed a charged debate about the state of American policing and shined a renewed spotlight on its role in the U.S. leading the world in mass incarceration.

Some argue that the system itself is broken, while others might deem Floyd’s murder abnormal and only existing on the fringes.

In no institution is this felt more than in schools, where social justice activists say that a reliance on on-campus police feeds the school-to-prison pipeline, which traps young people, disproportionately those of Black and Hispanic/Latino descent, in a cycle of criminalization that eventually becomes self-fulfilling.

Last year, both San Jose Unified and East Side Union school districts voted to end their partnerships with campus police because of this reason. At San Jose State University, student organizations have recently organized to ask their school to do the same.

Because community colleges are some of the last educational institutions in the state to return to in-person learning, the debate is just starting to get off the ground at De Anza College, which is situated in the suburban city of Cupertino.

When the Black Lives Matter protests broke out nationwide, the school was quick to issue multiple statements denouncing racism and began hosting multiracial panel conversations that continue to this day.

In these conversations, De Anza students started asking themselves if the school was living up to its goal of creating an equitable and safe educational environment, especially for those most negatively affected.

Tamara Williams, who graduated from De Anza shortly after the Floyd murder, spoke out first. She told La Voz that year of the harassment she endured at the hands of campus police, which declined to comment on her claims, and questioned whether or not the money spent on armed police officers could perhaps be redirected to scholarships and resources for Black students that were on the chopping block years earlier.

Today, those musings have carried over to actual student government policy stances, starting with the “Fund FHDA Students!” campaign which tried to stop the hiring of two new police officers for the district police department in late 2020.

In the current 2021-22 school year, the De Anza Student Government president and vice president both stated that de-funding or shrinking the on-campus police presence was a goal of their new administration.

“I see no real purpose of having campus police, especially knowing how uncomfortable they can make students of color feel after last year’s turmoil,” said Sarah Morales, who is vice president of DASG. “When it comes to campus security, we have to look at the root of problems and look for other options so that we don’t always have to rely on the police.”

DASG President Anahi Ruvalcaba told La Voz in November that she views the issue in almost a practical sense.

“Their main responsibility is handing out parking tickets,” she said. “We firmly believe the funding that goes to them would be better used on our students.”

In order to enact such changes, Ruvalcaba and Morales must work with faculty and staff, whose tenures will live on even after student leaders leave office or transfer to other universities.

When Lloyd Holmes was appointed as De Anza’s new president just days after the Floyd murder, he said that he recognized the moment and understood that as a “Black man who has lived the experiences of our many Black students, faculty and staff,” there was a need for “genuine change.”

But on the issue of maintaining or reforming the on-campus police presence, it appears that he already has strong disagreements with student leadership.

“If getting rid of the police is one of Student Government’s priorities, how did they get to that point if they’re supposed to be representing all of our students?” Holmes said.

He added that while the campus is not unsafe, he did feel that students could be lulled into a false sense of security when they “don’t really know what’s going on.”

“So I wonder what research you have done before you put the statement out there that signals that this is what all students want,” Holmes said. “It’s interesting, when I first got here, the people that were first stepping up to talk about their negative interactions with the police seemed to always be referring to experiences with San Jose Police. It was never our on-campus police that they were talking about.”

Holmes has the thankless task of balancing these two perspectives. On one hand, activists are asking that he and district leadership divert police funding to much needed student resources; on the other, he must define the scope of campus security with a limited police force and the return of students to campus.

De Anza shares its policing resources with its sister school Foothill College. Together, the two schools currently have about six officers and two sergeants.

Though students from both schools are still primarily in remote learning, campus police have handled a variety of incidents documented in their police blotter. For example, officers provide courtesy services, such as unlocking doors for professors, work security for sports games and investigate more severe offenses such as harassment or vandalization.

Marcus Carson is a police officer in the state of California and has been patrolling both the De Anza and Foothill campuses for four months now. He said that while things may appear slow to students who are not in-person, he and his colleagues are still relied upon both on and off campus.

“To be in law enforcement, you have skills that are perishable if you don’t use them,” Carson said. “So when there’s downtime on campus, I’m looking for things off campus to keep my investigative skills up to par.”

He added that he’s been assisting in handling DUIs on the freeways between the campuses and working to engage with students in preparation for their return.

“Instead of just sitting in the car, I try to speak to students whenever we come in contact, answer their questions and sometimes help them get somewhere they need to be,” Carson added. “I don’t feel that there is any sort of ‘hate’ from them. They’ve mostly been positive, so I do feel support from the students.”

Advocates for policing reform argue that there should be alternatives to armed officers responding to every incident. To lower the risk of fatal confrontations, they propose that the community of concern police themselves or at least collaborate with local authorities to de-escalate tensions or handle nonviolent issues.

At De Anza, parts of that thinking have already been implemented for quite some time. In addition to the eight officers mentioned, the department also staffs three unarmed “Community Service Officers,” commonly referred to as CSOs, and even hires student employees, known as “Police Student Aides,” or PSAs, to carry out administrative tasks and conduct patrols.

In this model, CSOs and PSAs act as sort of a buffer and only escalate issues to officers when there is something they cannot or do not know how to handle.

Khanh Vy Ho, 21, economics major, has served as a Police Student Aide since September 2021. She said that her superiors are “nice people” who do a good job preparing her to communicate with students and that they emphasize that her team be friendly to everyone “so that people feel good about letting us help them, which is the point of our jobs.”

“I think it’s great that the school has a police station. It means they really care about security and are investing in it,” Ho said. “In our staff, we have people who are Mexican, Russian, Vietnamese and French. We all really love and support each other. Racism is not a problem at our station.”

At its height, before the pandemic shuttered on-campus life, Ho said that the PSA team once staffed over 25 students, but today that number is closer to six or eight depending on availability.

As an international student with limited employment options, she said that the PSA job has helped her stay on track in school while supporting her financially. She also tutors part-time in the economics department and mentioned that she is allowed to study and do homework if work at the station is slow.

All of this to say, the question of how the De Anza community moves forward with this debate remains unclear.

The call to defund the police also comes at a time when the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed and exacerbated socioeconomic inequities. Some argue that police receive funding un-checked while the student government had to decrease its available budget and even went on break a week early this quarter, citing burnout from senators.

(Portions of the DASG’s operating budget are also affixed to revenues made from the De Anza flea market, which has been shuttered during the pandemic.)

Michelle Fernandez said she feels for both sides now that she has spent some time as student trustee to the district board for De Anza, bringing up student concerns to leaders that are actually in a position to implement change.

“As a person of color, I understand these negative feelings toward the police and would rather some of that money that funds them go towards us,” Fernandez said. “On the other hand, I understand wanting safety for our campuses. I have meetings that sometimes will end late at night and having that sort of presence on campus is important for me as a woman.”

She added that a change to on-campus policing does not have to be immediate, and that perhaps Foothill-De Anza can follow the footsteps of Peralta Community College which voted to gradually phase out its partnership with the local sheriff last year.

Until then, the De Anza students that have been advocating for police reform are left wondering what will become of their efforts as time passes and institutional memory fades.

“We can work as hard as we want, but most of us are not going to be here next year,” Morales said. “That’s why it’s hard to get things done. Many times, our agenda is just not consistent with who comes into these senate positions. So, after we leave, who continues to advocate for these specific issues?”