De Anza professor honored for activism embraces her Asian-American culture

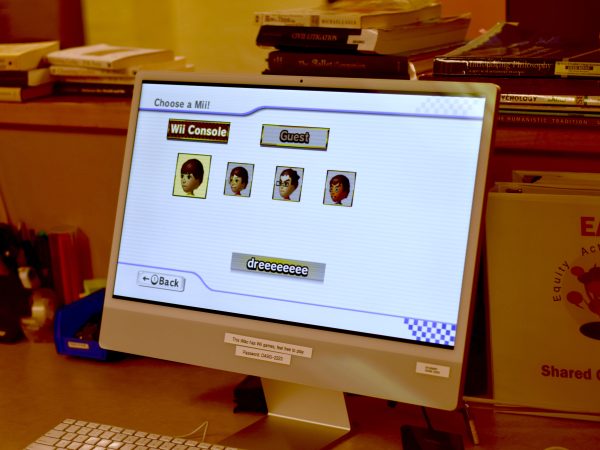

Ethnic studies professor Mae Lee was honored at Stanford University’s Multicultural Alumni Hall of Fame on Oct. 25.

November 13, 2019

Being one of a handful of Asian students at her school, De Anza ethnic studies professor Mae Lee recalled other children coming up to her, pulling at their eyes to taunt her appearance, mocking the Chinese accent which she recognized in her parents’ speech.

These were the elements of her life as a child of an immigrant family which she would later look back as she furthered her education.

She entered Stanford University during a time where Asian-American students and other students of color were participating in student-led activism.

Casual conversations with classmates resulted in her participation in a riot advocating for Asian-American and ethnic studies classes

“Here’s the irony, 30 years ago almost to the day, I participated in a student action which took over the president’s building and was arrested with 54 other students,” said Lee. “I never even got to take an Asian-American studies class at Stanford in my time there, and 30 years later I am teaching it and I am chair of Asian- American studies.”

It was not until she discovered the term Asian-American during her time at Stanford University, that she saw other Asian students and began to reconcile the two different parts of her identity: being Asian and living in the United States.

On Oct. 25, Stanford inducted De Anza professor Mae Lee into their Multicultural Alumni Hall of Fame for her involvement in student action at Stanford.

My parents weren’t wrong. I wasn’t wrong. But I received the message that someone who speaks like my parents is less than if they spoke standard, accented English,

— Mae Lee, ethnic studies professor

The term Asian-American became significant in defining her life experience in the United States.

“[This was] not because all Asians ate the same food or had the same religion or speak the same language because we don’t,” said Lee. “But it’s just because we’re racialized as a certain minority group in the United States that then we shared this same commonality.”

Lee graduated from Stanford in 1992 with a degree in international relations but did nothing with that degree.

She worked with different non-profit organizations, Americorps and City Year, which focused on engaging youth in public service, but realized she loved collective work and decided on teaching at the college level.

One day, she ran into Michael Chang, former Asian-American studies department chair at De Anza, who was looking to ll a part-time teaching position in the intercultural studies department.

She has since been an ethnic studies professor at De Anza for 20 years.

“For me, my journey is noticing what’s happening as every step along the way, and paying attention to what’s working for me, what I like,” said Lee.

She identified that now, higher education creates pressure for students to have a plan, which denies the opportunity for growth through self-discovery.