Students deserve ‘.edu’ email

October 23, 2016

Students shouldn’t have to demand technology in the Bay Area, but those at De Anza find themselves lacking a ubiquitous piece of technology: student email addresses.

“In order to obtain “.edu” email addresses for all students, we would expect to see a significant demonstration of broad support represented through student leadership – ideally the DASB Senate, or another organized and thoughtful approach with, again, widespread support demonstrable through a current and statistically significant survey or other means,” said Marisa Spatafore, Associate Vice President of Communications and External Relations.

However, in a 2013 study by the De Anza College Office of Institutional Research and Planning, four out of five students were found to be interested in obtaining a “.edu” email.

Given that the only stipulation is an evident display of support among students, there is absolutely no reason that De Anza, as a community college that espouses one of the highest transfer rates, should not grant “.edu” email addresses to its students.

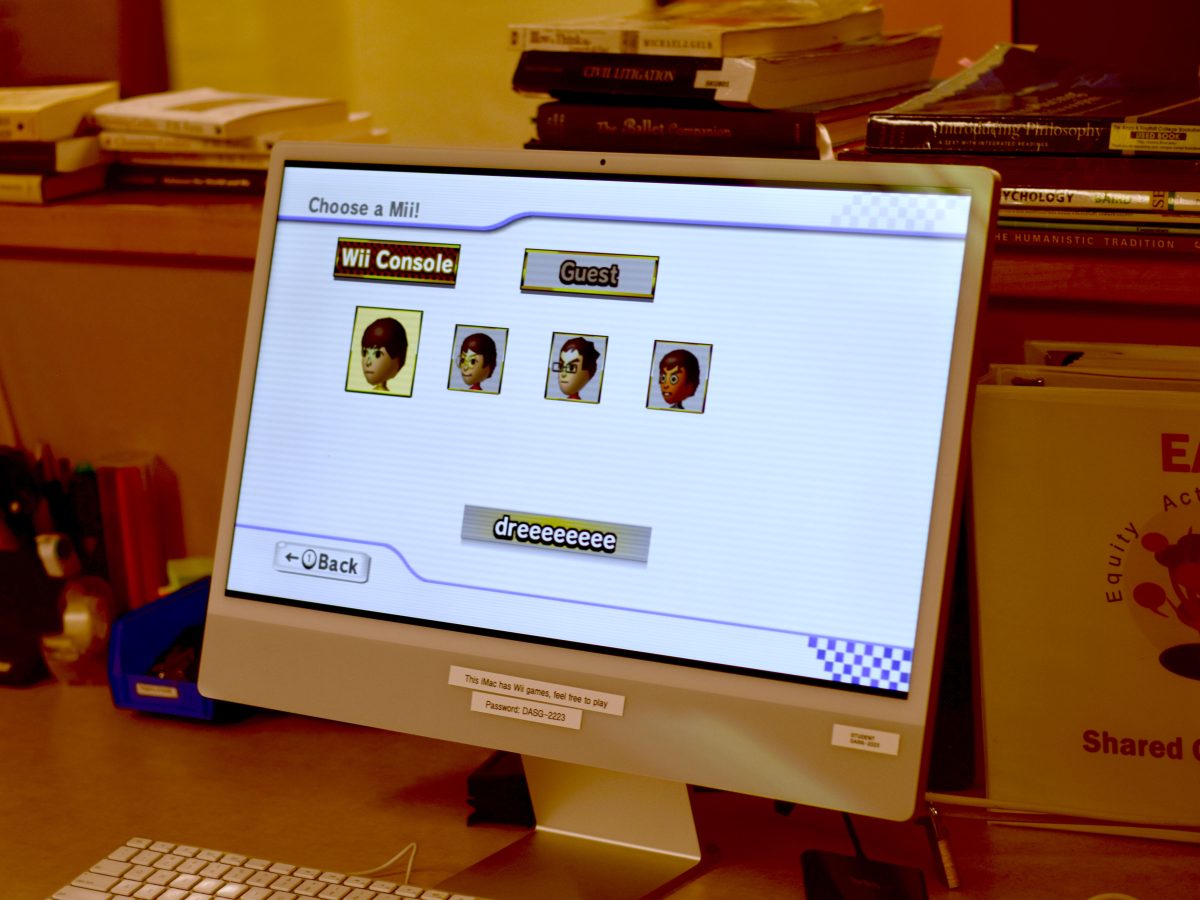

Of the many prospects which student emails provide, perhaps the most noteworthy is Amazon Prime, a quick shipping service which is bundled with accessible, free music, movies, and TV shows. Adobe, which has become well known for creating software pertinent to the advancement of students’ careers, also offers notable price reductions for its students. Additionally, Spotify Premium lifts the financial burden for students, and even the well-received New York Times offers a highly discounted one dollar subscription for students.

Imagine this common scenario from the perspective of a student. It’s the fourth day of the new quarter, and a hypothetical professor, let’s call him Gropis, has certain expectations you must meet. Besides the frankly absurd assumption that you will actually use Catalyst, a website that’s surely nothing else but a remnant of paleolithic times, there is an even greater desire for students to have already obtained the class textbook and to have read the first chapter.

All this transpires while students are uncertain about their class enrollment and unsure as to whether they are willing to spend $50 on a book they might not even need. Facing strenuous deadlines and high costs, it is unlikely any student is interested in paying a shipping cost that could have been avoided had students simply stood up and demanded student emails.

In fact, the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges, Western Association of Schools and Colleges already allows for De Anza faculty and staff to have “.edu” email addresses, exemplifying the fact that De Anza already meets the qualifications for hosting such accounts.

Employees in professional settings aren’t expected to use personal emails for work. Faculty and staff don’t have to use their personal email addresses at De Anza. And yet, we are told that students should. Within both academia and the professional world, different email domains portray a distinctly different set of presuppositions; @whitehouse.gov emits an aura of extreme ethos while @gmail.com could be Joe Shmoe on Miller Avenue. Having a student email is a statement of authenticity and dedication to businesses, future schools, and other beneficial connections.

“If there were a serious, organized request from current students, the Technology Committee could consider it, together with Central Services’ Educational Technology Services, which would need to implement the project,” said Spatafore.

Many other community colleges in California already provide email addresses to students.

The fight for student emails may seem either juvenile and unnecessary, but it is a palpable and meaningful fight that is within immediate reach — one that could assist students in furthering both their education and their careers.